Fall 2024 Featured Research Profile

Climbing the Economic Ladder, and Counting the Rungs: Economists Debraj Ray & Garance Genicot Explore a New Method to Measure Upward Mobility

Traditional economics has long divorced questions of economic growth from those of

economic equity. The (in)famous Kuznets Curve posits that, as countries’ economies grow,

inequality will rise but ultimately fall again. The prominence of this theory, and others like it, has

led mainstream economists of yesteryear to focus almost exclusively on growth, handwaving

away concerns about inequality as an unfortunate side effect that can be cured by more growth.

As appealing as that conclusion was, in the decades since the 1960s, developing countries

have seen significant increases in inequality despite sustained economic growth. This has led

many economists to foster a more nuanced understanding of growth, as potentially both inclusive

and exclusive, depending on how wide a subset of a country’s population shares in that country’s

overall growth. Though, understanding growth equity requires measuring it. One such area

economists are interested in measuring is upward mobility: the ability and frequency with which

individuals move to higher socioeconomic positions.

When it comes to measuring upward mobility, there’s good news and bad news. The good

news is that economists have developed multiple clever and statistically strong ways to quantify

this important area of interest. The bad news is that many of these measures require panel data. Panel data is a type of dataset that collects information over time from the same set of subjects,

whether it be people, companies, countries, or some other category. This type of data allows

economists to leverage powerful statistical estimation techniques, but is expensive and

time-consuming to collect, as it requires observations from multiple time periods on the same

entities. As a result, the reliable panel data on income and wealth that you’d need to estimate

upward mobility can be hard to come by, especially so if you’re interested in studying

developing countries.

This is where economists Debraj Ray & Garance Genicot come in. In their paper

“Measuring Upward Mobility,” the two researchers craft a mathematically robust and statistically

rigorous measure of upward mobility that is panel-independent – requiring only income or wealth

information across time, not necessarily from the same individuals. They start with a central, and

rather intuitive, assumption they refer to as Growth Progressivity, which assumes that an increase

in a poorer individual’s income growth rate relative to a decrease in a richer individual’s income

growth rate constitutes an increase in upward mobility. With this baseline, and a few other key

assumptions, Ray & Genicot are able to construct their new measure of upward mobility, which

turns out to be robust enough to accommodate dynamic population sizes and stratification by

social groups with only some minor modifications.

Not only do Ray & Genicot construct this new method, but they conclude their paper by

taking it to the data for three empirical test runs. The first concerns the work of famous public

economist Raj Chetty, who’s work on upward mobility relies on measuring the share of families

whose children earn more than their parents. While an appealingly intuitive measurement, this

method is panel dependent, and Ray & Genicot demonstrate that essentially identical conclusions

can be drawn using their measurement of upward mobility without using panel data. Ray & Genicot’s new method is justified formally via their mathematical proofs, but the fact that this

measure mimics the finding of a well-known panel-dependent study offers some informal

support.

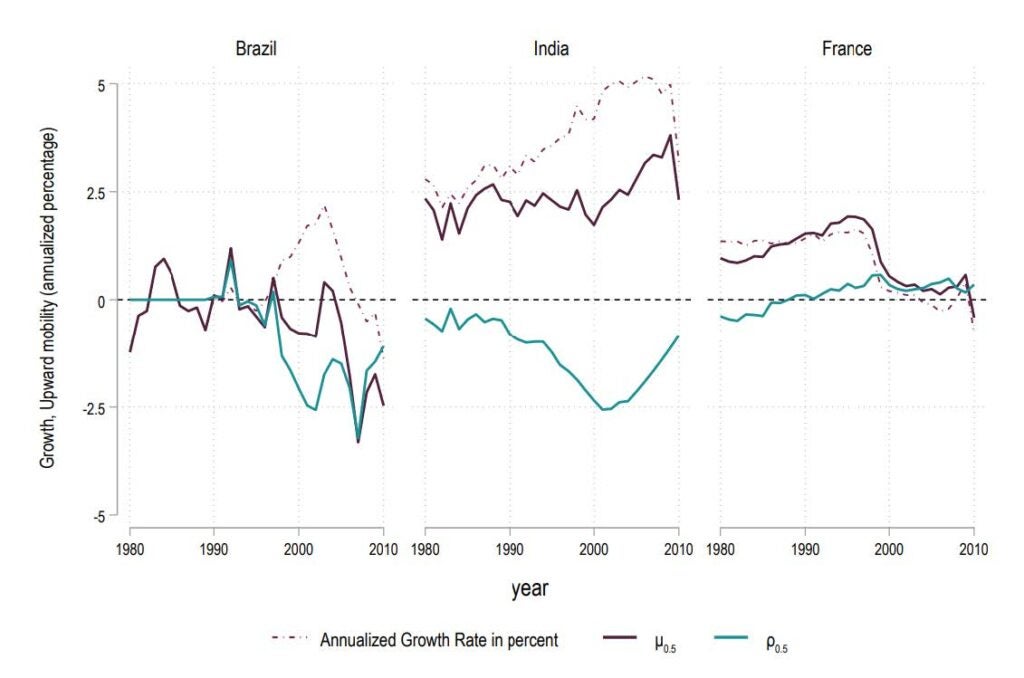

Emboldened by this support, the paper then covers new ground, by using its measurement

to investigate the upward mobility of a selection of countries where panel data isn’t widely

available. The paper looks at Brazil, India and France from 1980 to 2010, and concisely plots the

countries’ growth rate, upward mobility (μ), and relative mobility (ρ) all as annualized

percentages over ten-year periods, seen below:

Finally, the paper concludes by examining the “Great Gatsby Curve,” a plot made popular by

economist Alan Krueger that argued for a negative relationship between intergenerational

income mobility and income inequality. The curve is essentially a visualization of the argument

that, as a country becomes more unequal, it becomes increasingly hard for the poor if said country to advance their economic position generation on generation – the inequality acting as a

poverty trap that prevents upward mobility. Similarly to the first empirical exercise, Ray &

Genicot’s new method mimics the negative correlation finding of Krueger when looking at the

same countries. What’s interesting here is that, without the panel data restriction, when

expanding the set of countries to 71 the correlation actually becomes very slightly positive!

These three empirical examples are brief, but they offer a jumping off point for further

study. Not only does the new method mimic past reliable work on upward mobility, but it

expands the number of countries that work can be done in. And as the final example

demonstrates, this expansion into developing countries has the possibility.

Video link: https://open.spotify.com/episode/6NhNXdviPlF0i7niYWMwOx?si=Dyo-GAwERc6v6lexRCs84w